Extensive Bilateral Gluteal Necrotizing Myositis after International Cosmetic Tourism

Robel Beyene MD, Jeffrey Shupp MD, Anthony Shiflett MD, Chadi Abouassaly MD

BACKGROUND

Necrotizing myositis is a condition characterized by rapidly advancing , severe infectious necrosis of a muscle group or compartment with acute inflammatory infiltration, pain and tenderness, loss function of the affected muscles, and, if left untreated, septicemia and death (1). Myositis can be idiopathic, or can be secondary to local trauma, malignancy or ischemia (2). While this condition is rare in the United States and other developed nations, it is more common in developing nations and in the tropics (3). As Americans increasingly look to cost competitive, offshore and international options for surgical care, they expose themselves to a different risk profile in many aspects, including the native microbiome of their host nation (4). International cosmetic tourism has grown significantly due to the cost savings and accessibility offered in some markets. As this trend burgeons, patients are returning to their developed nation homes with complications and sequelae from low cost surgeries done abroad, including various surgical infections. Necrotizing soft tissue infections are among the complications seen with increasing frequency in the United States and other developed nations, after international cosmetic tourism.

PRESENTATION

A 44 year old woman presented with a one week history of persistent, unbearable pain and tenderness in her bilateral buttocks and right, lower flank. This episode began following abdominoplasty, liposuction of her bilateral thighs, and bilateral gluteal fat injection in the Dominican Republic, one week before presentation. While her abdominal incision had become less painful, her buttocks and flank had become more severe each day after surgery, until the patient was no longer able to ambulate freely.

PMHx: Hypertension, Type II diabetes mellitus

PSHx: Hysterectomy

SHx: She denied a history of smoking, but did drink occasionally

PHYSICAL EXAM

On initial exam, the patient was tachycardic to 139, with a blood pressure of 136/62, and a temperature of 37.6ºC. She had a well approximated transverse, suprapubic incision with mild serosanguinous drainage. She had no open wounds or erythema of either buttocks, but both were very firm and exquisitely tender to any palpation. There was bilateral crepitus.

ASSESSMENT

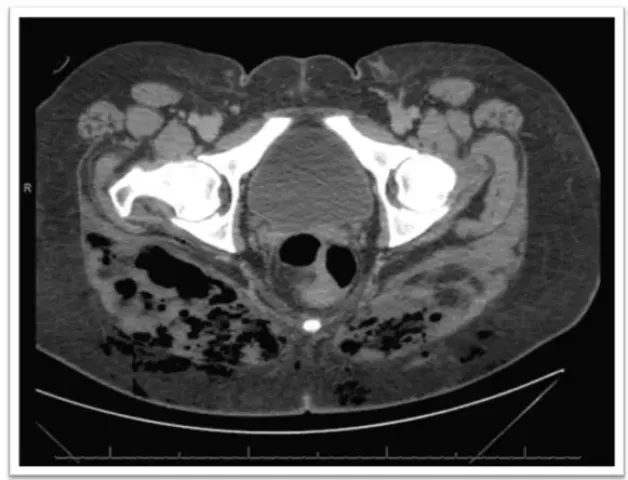

Lab results showed a leukocytosis of 22.4 thousand/mm3. The patient’s sodium was 135 mEq/l and her lactate was 2.2mmol/l. A CT scan was notable for significant air in the deep soft tissue and throughout the musculature of her buttocks, bilaterally, and her lower, right flank. After the ruling out the possibility that the CT findings were normal after gluteal fat injection, the patient was diagnosed with a necrotizing soft tissue infection.

HOSPITAL COURSE

Central venous line, urinary catheter, and broad spectrum antibiotics were all continued, along with fluid resuscitation. In the operating room, upon incising the fascia overlying the right gluteus maximus, a large volume of foul smelling, necrotic fat was expressed. The incision was broadened and another incision was made on the contralateral side, exposing large sections of necrotic muscle and fat, including portions of the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and piriformis, bilaterally. All areas of necrosis were excised or debrided and a sterile dressing was placed over the wounds. After several return trips to the operating room, along with the reconstructive surgeon, the patient eventually did well enough to be transferred out of the ICU and to the wards with a negative pressure wound therapy device. Her operating room cultures grew few, multi-drug resistant, staphylococcus epidermidis.

RESULTS

The patient had her surgical wounds closed by the reconstructive surgery team and was discharged home on hospital day 10 in stable condition. She continued to follow up with the reconstructive surgeon, who eventually performed and buttock augmentation on her.

DISCUSSION

The very nature of international cosmetic tourism makes it difficult to calculate the potential risks and benefits (5). The cost savings and accessibility make it both attractive to the consumer and laudable in its own right; however, these benefits may come at the cost of appropriate pre-surgical evaluation, post-surgical management, patient safety, and the oversight, accountability, and record keeping to support those tenets of surgery commonly seen in developed nations (6). Furthermore, as complications arise, patients are either turned away from or lose faith in these low cost options and return to their developed nation homes for care, with little hope of reaching their surgeon abroad for information or records to aid in their care (7). In a survey of Canadian physicians, 41% of the physicians who had encountered such patients responded that patients presented with insufficient information about their treatment abroad (8). A survey of US medical tourism companies found that 91% of the companies gathered patient satisfaction data, while only 50% collected patient outcome data (6). In developed nations, this data is routinely collected and complications are commonly taken back to the operating surgeon responsible.

Almost every published study on international cosmetic tourism lists cost savings as the primary driver of the industry. Arguments have been made that outsourcing certain procedures to low cost, international hospitals could save billions of dollars from the US budget and defray Medicare spending (9). These calculations, however, assume equipoise between all care facilities. As patients are more likely to have complications treated in their native countries, those developed nations essentially underwrite procedures done abroad by guaranteeing emergency care to its citizens. This suggests that, while the unit cost of cosmetic tourism may be lower, the societal cost may not be. A small UK study by Miyagi et al. showed that hospitals treating these patients did so at a financial loss, while Hanefeld et al. calculated cost of £ 8.2million per year for all such patients in the UK (10, 11).

The most common complications following international cosmetic tourism are infectious complications, which will likely continue to increase as cosmetic tourism grows in popularity. This is partially driven by high background rates of certain infections, such as tuberculosis, Hepatitis B and C, and HIV, in some tropical and subtropical cosmetic tourism destinations (5). This, along with variations in drug resistance profiles and questionable sterile practices, leads to increased risk of infection. It is the responsibility of American surgeons to understand the needs, and unique risks of these patients, as well as the systemic driving forces and repercussions of international cosmetic tourism.

REFERENCES

- Bharathi RS, Sharma V, Sood R, Chakladar A, Singh P, Raman DK. Management of necrotizing myositis in a field hospital: a case report. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:20.

- Brook I. Microbiology and management of myositis. Int Orthop. 2004;28(5):257-60.

- Nather A, Wong FY, Balasubramaniam P, Pang M. Streptococcal necrotizing myositis: a rare entity. A report of two cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987(215):206-11.

- Milstein A, Smith M. America’s new refugees–seeking affordable surgery offshore. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(16):1637-40.

- Chen LH, Wilson ME. The globalization of healthcare: implications of medical tourism for the infectious disease clinician. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(12):1752-9

- Alleman BW, Luger T, Reisinger HS, Martin R, Horowitz MD, Cram P. Medical tourism services available to residents of the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(5):492-7.

- Birch J, Caulfield R, Ramakrishnan V. The complications of ‘cosmetic tourism’ – an avoidable burden on the NHS. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60(9):1075-7.

- Runnels V, Labonte R, Packer C, Chaudhry S, Adams O, Blackmer J. Canadian physicians’ responses to cross border health care. Globalization and health. 2014;10:20.

- Boyd JB, McGrath MH, Maa J. Emerging trends in the outsourcing of medical and surgical care. Arch Surg. 2011;146(1):107-12.

- Miyagi K, Auberson D, Patel AJ, Malata CM. The unwritten price of cosmetic tourism: an observational study and cost analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65(1):22-8.

- Hanefeld J, Horsfall D, Lunt N, Smith R. Medical tourism: a cost or benefit to the NHS? PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e70406.